The Double Cone of Media Literacy

2024-09-09

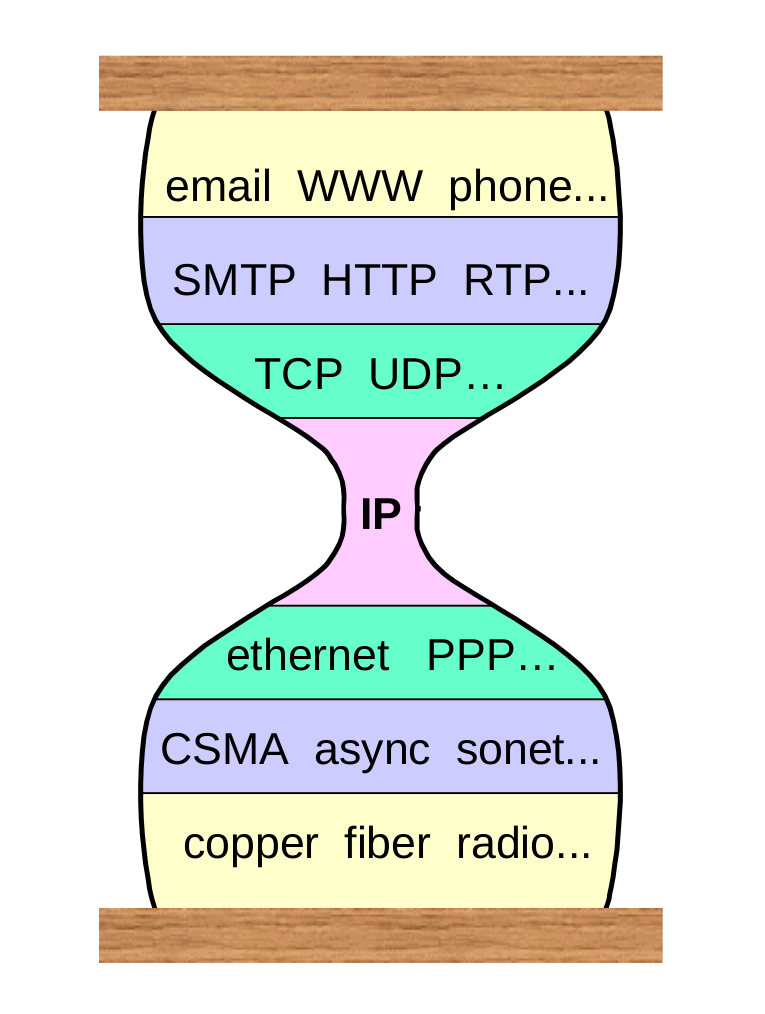

Computer Science students who study networks see this diagram, entitled the hourglass" or the thin waist of the internet.

The text after this picture states that there are many protocols at the base of the internet, and many protocols at the top, but much fewer in the center.

If you're confused by what a "protocol" is, think of it as a procedure used to communicate information. Higher level protocols encapsulate lower level protocols. Sign language, grunting, and texting would all be examples of real-life protocols. Just like in the diagram, these protocols build off of each other; we use the making-sounds protocol for the forming words protocols, which we use for the making sentence protocols, which can be used to make speeches, requests, or conversation. There are multiple ways to build up to a higher level protocol. To ask someone for a favor, you could gesture to them, text them, or speak to them. To speak to someone, you could phrase it in different ways or even speak a different language.

The thin waist stems from the ubiquity of the IP(internet protocol), which is used almost universally. No matter how you build up your "sounds," you will need to send some information through this protocol.

I want to use this metaphor to explain media literacy and how it affects the consumption of both non-fictitious and fictitious media, and why media literacy is important. So let's rotate the hourglass.

The left side of the hourglass represents reality. In journalism, these are actual events or ground-truth facts (such as, Lee Harvey Oswald shot a bullet in November of 1963, or caffeine consumption increases alertness in humans for several hours after consumption). For fictitious media, there is still a ground truth, albeit only in the author's minds eye. They imagine a scene in its entirety before they put pen to paper.

To show off this artificial reality, the author provides a magnifying lens to give the illusion of a complete plot in order to provide the right half of the diagram--- the story. The story is a cohesive narrative which uses the plot and its context to tell something greater than the sum of its parts. The story is the "why" to the plot's "what." A story would be "Lee Harvey Oswald assassinated JFK independently" or "drinking coffee will improve your morning." A story is birthed by rhetoric expertly managing facts as actors on a stage.

Media literacy is a complicated and loaded term. I was fortunate enough to stumble across a video by Zoe Bee which covers this exact topic. She grapples with the vacuousness of the term and its definitions, which essentially boil down to using a variety of skills to question the work in front of you. I don't think there is a succinct definition, at least without sacrificing completeness. What I arrived at after watching her video is a willingness to wrestle with a work during and following the process of consumption.

In the hourglass diagram, this corresponds with moving the central point. The author has written a book or a movie, a single accounting of a infinitely complicated event. Research has shown that two witnesses to the same crime can give wildly different accounts

On the left, we have all of the facts; however, the only ones that are visible lie within the cone that the creator has let the viewer observe. There will always be facts or events that lie outside of that cone.

The bottleneck is entirely in the hands of the content creator. They cannot control the right side--- any story has a multiplicity of interpretations, contexts, and readings. It exists in the readers mind, not in pages or video.

Someone with media literacy is able to manipulate this bottleneck to magnify the work or be critical of it. They can focus on the portions of the plot highlighted by the author in order to twist the lens into a mirror of that author and their desired message. They can reach beyond the cone into the darkness and extrapolate that which might be there that would change or modify the core message. They can add their own lens and recontextualize past works in the modern era by adding context that was unknown at the time of creation.

There's enough literature to motivate why having media literacy is important. What I'm hoping to highlight here is how small the bottleneck is; for many articles and books, it is as little as two people. When we look through the glass at the other side, we can only see the cross-section that the author has given us. In some cases, it may be possible to find another viewpoint and cross-evaluate the original author's veracity, but this is a privilege granted rarely in nonfiction--- and then mainly in free-press countries--- and never in fiction. There may only be a single journalist breaking a story, or a reader might have to trust the word of a dubiously sincere nation-state. If there is no other authority you can rely on, media literacy is the only weapon of self-defense in your holster.

And it's a dangerous world out there.

Credit: Zoe Bee, "YouTube and the Death of Media Literacy"